Since the 1940s, the brilliant minds at GE Aviation’s facility in Lynn have been revolutionizing air travel. By Scott Kearnan

Â

It’s the american dream: Build something big out of something small, watch it take flight, and then be rewarded by moving up a chain of command. But in the information age, when many people are pouring their sweat and elbow grease into cyberspace instead of onto an assembly line, that sort of sentimentality sounds hopelessly nostalgic.

You might think you’d have to time travel back to Mayberry to see such old-school ingenuity in action. Instead, set your coordinates to Lynn, home of one of the original GE Aviation facilities. It was here in the early 1940s that General Electric revolutionized air travel by designing, manufacturing, and demonstrating America’s first successful jet engine.

Now, over 70 years later, GE Aviation has become the world’s leading producer of jet engines for commercial and military aircraft. Its Lynn plant is a centerpiece to the local economy; it employs 3,200 workers, making it the largest employer in Lynn and one of the largest on the entire North Shore. It continues to develop groundbreaking products while functioning as a reminder of milestones in aviation history.

One man preserving that history is David Carpenter. The Danvers retiree has written six books on GE Aviation’s Lynn facility and is the curator of the plant’s Jet Pioneers Museum-a small but tenderly cared for space where a timeline of engines and other machines shows the evolution of the company and its technologies. Carpenter is a walking encyclopedia of aviation, able to fire off facts, figures, and engine model numbers in the way some people spout baseball stats. But there is also an earnestness with which this warm and friendly man reflects on the company, his time there, and his responsibility of documenting its history. “When a place educates you, gives you a good life, cares for your family’s health-you have to give back,” he says, smiling.

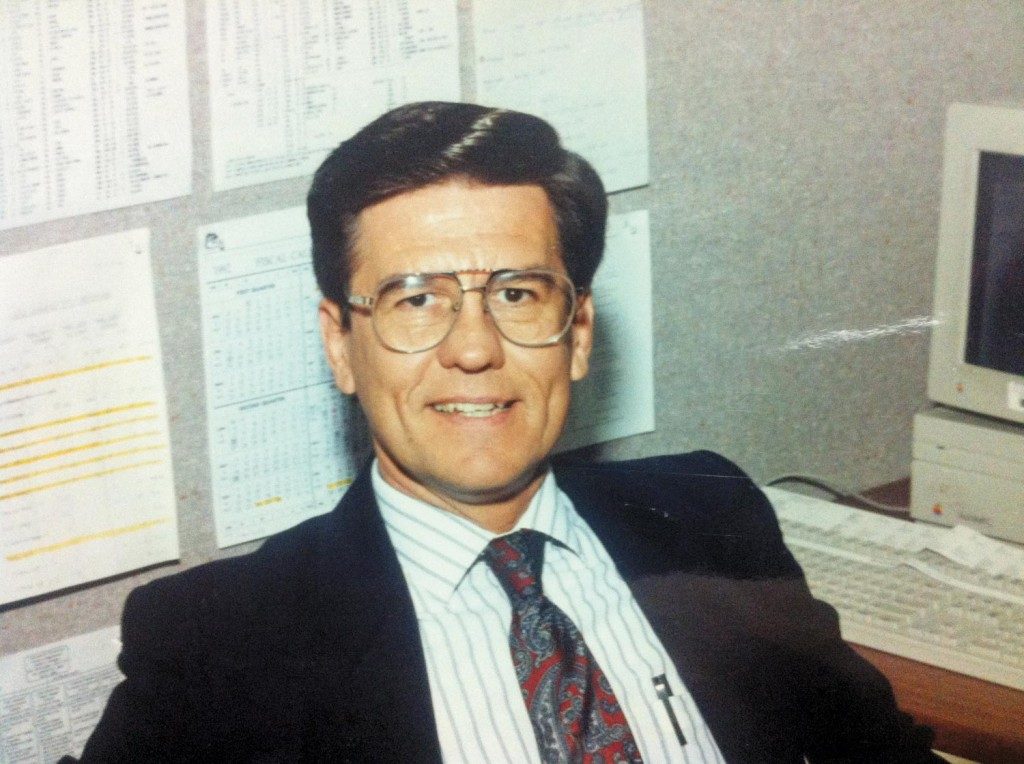

David Carpenter on the job at GE Aviation in earlier days

In 1963, Carpenter moved down from Maine to take part in an apprenticeship program that GE’s Lynn facility ran from about 1897 to 1989. General Electric was born (well, sort of) in Lynn, formed by an 1892 merger between the North Shore plant and a New York facility, and it played a huge role in the Second Industrial Revolution. For decades, GE’s renowned apprenticeship program lured young people like Carpenter to the Lynn plant, which by the mid-1940s was dedicated to GE’s aviation manufacturing. “Poor boys from Maine and locally, who couldn’t afford an education, would come here,” says Carpenter. In Lynn, the apprentices would be exposed to everything from management training to the manufacturing floor, where workers built and tested engines for military aircraft and commercial airplanes. GE paid Carpenter’s way through Northeastern University, and by night he worked at the plant.

Carpenter also worked his way up. His first job, while he waited for the apprenticeship program to start, was at the bottom of the totem pole. “They told me I was going to be a servicer. I thought that meant I’d be checking oil and filters,” he chuckles. “Basically, I was a janitor. I took out the trash.” By the time he retired in 1999, Carpenter was a sales manager. Now he continues to volunteer as its historian, a keeper of its place in the community. “Working here was like working for your mother. [GE] was good to me,” explains Carpenter.

It’s that kind of nose-to-the-grindstone American work ethic, the kind that can build a career from scratch or an engine from thousands of parts, that keeps GE Aviation in Lynn a vital business. The rambling campus off Route 107 stretches over 220 acres and contains over 20 buildings. The “city within a city,” as Carpenter calls it, has boasted everything from a 12,000-square-foot health and fitness center to a restaurant and auditorium; at one point, it even produced its own weekly newspaper. But most important, of course, is its manufacturing space-all 1.5 million square feet of it. The facility creates specific parts that are supplied to other GE Aviation facilities and it designs, produces, and assembles entire aircraft engines from start to finish.

Of course, engine model numbers may not be as recognizable as a brand name, like Pepsi, and they don’t come with snazzy slogans, either. But you’ve probably reaped the benefits of GE Aviation’s creations without even knowing it, as products for commercial jets represent about a third of what comes out of Lynn. That includes the CF34 engine, launched by GE in 1992 and credited for kick-starting the commercial regional jet industry. It’s now the best-selling engine of its kind, with over 5,000 in use today. That means that somewhere in the world, one is lifting off the ground every eight seconds, according to GE. In fact, if you’ve ever hopped a regional flight on a major carrier such as Jet Blue, your trip was probably powered by a CF34.

Assembling the F414 engine

Assembling the F414 engineThe other two-thirds of products created at the Lynn plant are for military aircraft. That explains why the building-which, from the road, could be mistaken for a prison complex -is so highly secure. (In a post-9/11 world, background checks are required for visitors like customers and suppliers to get inside certain buildings, while employees can only access areas based on their restriction level.) The F414 engine is built soup to nuts here; it powers the military’s famed Apache and Black Hawk helicopters, the Navy’s Super Hornet fighter jet, and the T700, the most popular medium-sized helicopter engine in the Western world.

In addition to the building of these cornerstone engines, development of new technologies is always happening at Lynn, says the facility’s spokesperson Richard Gorham. The site’s engineers are a think tank that is constantly buzzing with ideas on how to create new materials, parts, or products that are more powerful, more durable, more fuel efficient, and greener than the last. The best new ideas might become prototypes used in pitching clients, such as the U. S. military. It’s those successful pitches that result in the multi-year, multi-million-dollar contracts that keep GE Aviation purring like one of its own engines.

More importantly, the products developed in Lynn keep America’s servicemen and women safe, says Ralph Gray. Gray has worked in the engine assembly area for 28 years, building and prepping for inspection engines like the T700. He says what keeps him motivated are the stories he hears from customers who have experienced firsthand the value of his work on the line. He was visited by an army sergeant who was critically wounded in the Middle East but was saved by a chopper with a GE Aviation engine. He’s heard stories about how overhauled parts have helped add 50 knots of speed to an aircraft, which makes a big difference when you’re evading enemy fire. And he’s seen with his own eyes the battle-worn yet still-working parts from returned aircraft that were able to return their pilots along with them. “When you realize [service men and women] came back because of the product you made, it’s a proud moment,” says Gray, sporting a sweatshirt with an American flag and the words “Support Our Troops.”

But Gray also feels loyal to GE Aviation because of the support it showed to him, he adds. Though he was once laid off, the company rehired Gray when it was able to do so. GE took that loyalty a step further when Gray’s 13-year-old son became infected with Triple E, a virus with a high mortality rate. It was a serious situation; his son had severe brain swelling and was put into a medically induced coma to prevent irreversible brain damage. He spent 20 days in Boston’s Children Hospital and required regular rehabilitation after his release. Throughout the ordeal, GE gave Gray as much time as he needed to be there for his son.

“It was no questions asked. It was just, ‘Go take care of your family,'” says Gray, tears welling in his eyes. “I get emotional talking about it, because I don’t know if many businesses would do that.”

Then again, a company that thrives on a good old-fashioned American ethos would certainly include support of family values as one of the perks. geaviation.com. ?n