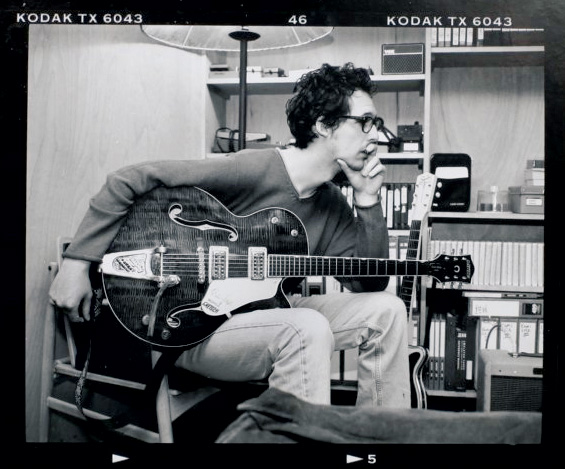

Marblehead’s George Howard is bringing digital music forward—by going back to basics. By Scott Kearnan – photographs by Tim Cook

Authenticity. it’s an important word to George Howard.

Howard stands at the kitchen counter in his Marblehead home, whipping up an all-natural smoothie of fresh fruits and veggies. “You should try one,” he says. Howard is a healthy guy; he starts every day with a run, practices yoga, studies Buddhism, and consumes a mostly raw, vegan diet. It’s a restorative lifestyle that helps him stay energized and balanced as he juggles life as a husband and father with a wide professional repertoire.

Nowadays, Howard is mainly focused on his work as COO of Norton LLC, the parent company of Concert Vault, Wolfgang’s Vault, Daytrotter, and Paste magazine, each a unique property in a music empire. Throughout his storied career, Howard has had a hand in nearly every aspect of the music business; he’s run a seminal record label, managed major artists like Carly Simon, and helped found TuneCore, now the world’s largest distributor of digital music.

Howard pops kale and kiwi into the blender; it whirs, stirring up a green tornado. He pours the mixture into a glass. “Here you go,” he says, handing it over. “If you don’t like it, I won’t be offended.”

It’s tasty. Really green—but tasty. And unmistakably unadulterated—an earthy flavor that could only be made by Mother Nature. It makes sense that Howard would place such a premium on organic eating. Whether in food or business, he appreciates what is authentic, and he uses each of his innovative ventures as an opportunity to buck an outdated music industry that too often exploits performers, turns art into assembly-line merchandise, and feeds consumers manufactured claptrap.

“Eventually, you have the same reaction to over-processed music that you do to over-processed food,” explains Howard with a smile. “You get sick of it.”

“Eventually, you have the same reaction to over-processed music that you do to over-processed food,” explains Howard with a smile. “You get sick of it.”

Music Business Beginnings

Howard was born in North Carolina and grew up in Philadelphia; he came to New England to study English literature at Boston University. But he was also writing music, playing guitar, and gigging with bands in the teeming early-’90s rock scene, one that predated Kurt Cobain and Co.’s ushering of grunge into mainstream pop culture. “It was pre-Nirvana, and the last gasp of true indie [music],” recalls Howard, kicking back by a crackling fireplace in his living room. His tone is slightly professorial, which makes sense; he teaches management at Berklee College of Music. But he has a sense of humor, too. Before long, he’s demonstrating his skateboard skills, and tumbling head over heels into a yoga pose.

“It was an awesome, creative time,” he continues. “I was surrounded by all these insanely talented people.” Among them was college acquaintance Mary Timony, who went on to play guitar and sing in the post-punk bands Helium and Wild Flag. “I remember listening to her play and thinking, ‘More people need to hear this.’”

Though he had already been pressing vinyl records, it was during post-grad studies at Brown that Howard officially launched his own record label, Slow River, in 1993. It released a number of successful singles, and signed the popular band Sparklehorse. Soon larger labels, looking to capitalize on the exploding indie-rock genre, were making Howard lucrative offers to release his Slow River records. Though those with “bigger pocketbooks” came calling, Howard chose to work with the North Shore’s Rykodisc. It had especial credibility among artists, and Rykodisc, then based out of Pickering Wharf in Salem, was the first CD-only record label. That unique combination—respect for musicianship and forward-thinking innovation—was attractive to Howard.

In 1999, 30-year-old Howard was named president of Rykodisc by its new owner, Chris Blackwell, the music industry pioneer who founded Island Records and signed legends like Bob Marley and U2. Howard ran Rykodisc out of Gloucester, where he lived, and remained there until 2003, when he left amid another transition in ownership. But a non-compete clause in his contract prevented him from moving to another label. Cue the sound of a record screeching to a halt.

A Different Tune

Stepping outside the label world was an abrupt transition. “Since I was 19 years old, my job was putting out records,” says Howard. “That was all I had ever done.”

But he found other ways to employ his music industry expertise. He wrote his first book, Getting Signed!: An Insider’s Guide to the Record Industry. He started teaching management courses: first at Northeastern University, then Berklee—and then, after moving to New Orleans for several years, at Loyola University. It was a pretty good time for a professional detour. In the first decade of the new millennium, record labels were struggling to keep up with a technological revolution. CD consumers were replaced by a generation that freely file-shared MP3s, and the consequences were devastating for labels and artists; according to Forrester Research, annual revenue from U.S. music sales plummeted from $14.6 billion in 1999 to $6.3 billion in 2009.

“The record business was imploding,” says Howard, calling the mid-’00s “dark days” for artists. They lost sales to illegal downloads as labels, which obstinately resisted every format change—from cassettes to CDs and now to MP3s—and failed to innovate approaches to distribution. At the same time, new software like Pro Tools gave independent artists a cheap, easy way to make professional-grade recordings, which robbed record labels of a big bargaining tool. Previously, labels offered to fund expensive studio sessions for artists; in exchange, they owned the master recordings and paid artists slim royalties. There were suddenly fewer incentives for artists to work within the outmoded label system.

It was that environment into which Howard helped launch TuneCore in 2005. TuneCore offered independent artists the opportunity to place their music on iTunes and other online retailers. “TuneCore helped solve the biggest problem for artists, which was distribution,” says Howard. And whereas similar services took back-end percentages of sales, TuneCore charged artists a flat fee for its service. “Keep what you sell,” says Howard of the ethos that helped turn TuneCore into the world’s largest distributor of digital music.

Despite an increasingly crowded marketplace, it’s now easier than ever for unsigned artists to release music. But developing TuneCore is hardly the only way in which Howard has helped musicians—and fans—embrace new digital worlds.

George Howard with Carly Simon

A New Day

In many ways, it seems like the music industry is on the verge of another major change. Recent years have seen an explosion of subscription-based services, like Pandora and Spotify, which allow users to stream unlimited music to home entertainment systems and mobile devices. There’s no need to buy albums or songs; users simply queue up tunes on demand.

Howard isn’t a fan of what that means for music. “Something that upsets me, and that I’m trying to change, is that music has become devalued,” he says, adding that those services are filled with the same catalogs of ubiquitous hits, mainly by bubblegum artists like Katy Perry and Justin Bieber. The streaming model has encouraged a proliferation of mass-market Muzak: “Commodified wallpaper,” he calls it.

Enter Daytrotter, one of several Norton companies that Howard helped develop—first via his own consulting firm, Rock and Roller, and today as Norton’s COO. Daytrotter’s website offers its members streams and downloads of songs by hipster-friendly rock acts, both established names and emerging up-and-comers. But unlike other, interchangeable online music stores, Daytrotter boasts a catalog that is totally unique to its service. Participating artists stop by The Horseshack, a cozy studio in Rock Island, IL—a small city three hours west of Chicago—to rerecord their songs exclusively for Daytrotter members.

Daytrotter, which had been early to discover future stars like Mumford & Sons, fun., and The Lumineers, has compiled over 2,400 sessions since launching in 2006. These unique recordings eschew the bells and whistles of high-gloss studio wizardry in favor of intimate, stripped-down versions that ring with artistic authenticity. “I don’t want to create the musical equivalent of air freshener,” says Howard.

These special recordings offer more than artsy credibility for performers. Other streaming services, like Pandora and Spotify, cannibalize the music industry, says Howard; why would fans ever buy a record when they can listen to it over and over again for free? Plus, the per-stream payments to musicians are just fractions of pennies. Yet the services would like to pay out even less; they’re pushing Congress to pass the Internet Radio Fairness Act, a bill that critics like Howard say is an unconscionable attempt to slash the already-microscopic royalty fees owed to working artists.

Howard says Daytrotter sessions don’t supplant an artist’s existing recordings; they instead offer distinct additional versions. The artists might join Daytrotter on national “Barnstormer” tours, getting paid to play barn venues across the country. Daytrotter will often press limited-edition vinyl records, replete with original artwork and liner notes, and split sales with the band. According to Howard, vinyls are enjoying a minor comeback among music aficionados who miss having a tangible testimony to their fandom in an era where most music lives in a digital cloud. That also helps explain the success of Wolfgang’s Vault, a Norton company that bills itself as the world’s largest store for music memorabilia.

Howard knows that the rootsy vibe of Daytrotter won’t appeal to every music consumer; after all, compared to the music super-malls of Pandora and Spotify, it’s a niche boutique. But its innovative approach offers real benefits to artists, he says, and serves a growing audience of listeners who are tiring, at least for now, of manufactured pop.

“Look at this year’s Grammy nominations,” says Howard. Mumford & Sons, The Lumineers, and fun.—bands that Daytrotter featured several years ago—all received nods. “We reach these cultural moments where we can’t take it anymore. How else to explain Mumford & Sons, four guys from Britain playing banjos, selling millions of records? That is the culture saying, ‘Quit it with this manufactured stuff.’”

Luckily, Howard is ready to hand it a kiwi-kale smoothie, so to speak, which might just do the trick.

Super Producer As COO of Norton LLC, George Howard has his hands in a lot of projects. Here, a breakdown of each and what they’re all about.

Concert Vault

Cheaper than a time machine, Concert Vault unlocks access to hundreds of audio and video recordings from live concerts at legendary venues. Name an era, name an artist, name a stage; if YouTube is a digital junk heap, this is a finely curated museum of music. wolfgangsvault.com/concerts

Daytrotter

This unique digital music store is an antidote to overplayed Top 40. Big-deal bands like Vampire Weekend and Mumford & Sons rearrange and re-record their songs exclusively for Daytrotter members, who score virtual entry to intimate jam sessions with favorite artists. daytrotter.com

Paste magazine

This music-focused digital magazine attracts over 2 million monthly visitors, combining mainstream entertainment coverage with an indie sensibility, plus a knack for finding emerging artists that are bound to, well, stick. pastemagazine.com

Wolfgang’s Vault

With over 25 million individual items—concert tees, original posters, ticket stubs, you name it—this is Ground Zero for music memorabilia collectors, not to mention casual fans in search of a cool gift. wolfgangsvault.com