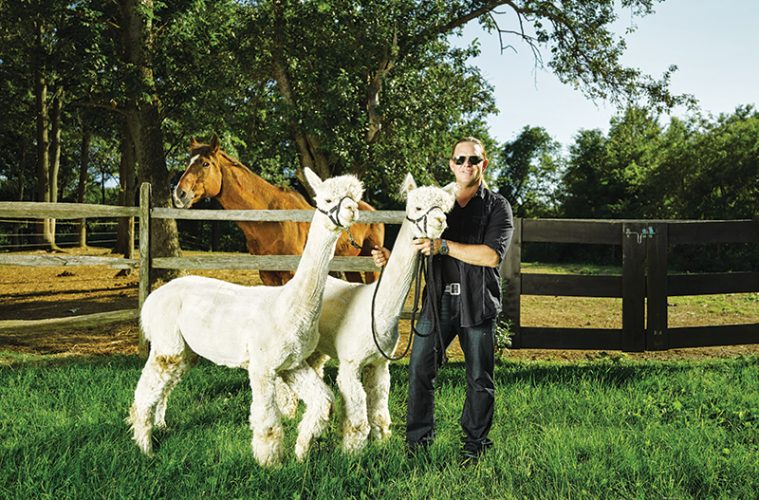

“Sheep are so familiar. Alpacas are a relatively new concept,” says Melanie Cosgrove, nodding to the pack of animals she and musician Pat Badger keep. “They are very docile and easy on the environment,” says Badger, with obvious affection for the 10 alpacas inhabiting their West Newbury farm.

“We call this the fraternity, and the sorority is down below,” explains Cosgrove, pointing to two separate paddocks. “The boys hang out on the hill and keep watch over the girls.” In fact, the four males and six females—all of whom have been named—rarely comingle, as breeding is not why the couple keeps them. “It’s planned parenting,” laughs Badger. They have bred them in the past, but they talk about the commitment it requires. There’s an 11.5-month gestation period and a two-week window when you have to be available for the birth, and then there’s special care needed during the first year of life. However, both of them light up when talking about “the babies,” and it is clear there will be more to come…at some point.

Alpacas are from the Andes Mountains in South America and are found in high altitudes of Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, and Chile. They were once treasured by the ancient Inca civilization, which used the prized fibers to make garments for royalty. The United States began importing the animals in the 1980s. “They were once so rare, but now they are becoming increasingly popular,” says Badger. The use of their fleece, however, is still a niche market. “It’s not like the fiber has become a viable commercial [commodity], because there aren’t enough alpacas in the U.S. yet,” he explains. In Peru, the alpaca population numbers in the millions and supports a thriving export industry. Here, it’s primarily hobbyist knitters and hand-spinners that use the fiber, although alpaca products are starting to appear in larger outlets like L.L.Bean. “It’s soft like cashmere, but warmer than wool,” says Badger, explaining that the “scales” on the fibers lay flat on alpacas, unlike those on sheep’s wool, which is what makes the former smooth and the latter more prickly.

Badger started this venture on his own back in 1995, when he was looking for something completely different from the music industry, which he had left after a successful run with his now-reunited band, Extreme. At the time, he owned a farm with an empty barn and paddock in Groveland. “As silly as it is, I saw an ad on CNBC for the world’s finest livestock investment,” he recalls. “It intrigued me because I already had the setup. I started visiting a lot of farms, made a lot of friends, and suddenly I had 30 alpacas.” He raised, showed, and sold them around the country back in those days. Today, it is their fiber that interests him more.

Alpacas can acclimate to extreme conditions of heat and cold. “We’ll come out in the wintertime, and they will have about six inches of snow on their backs, and they don’t seem to notice,” notes Cosgrove. Prime fleece is on their “blanket,” which covers the area from their bellies to their mid-back—leg and neck fiber is coarser and not generally used. There are two distinct breeds of alpaca: Huacaya, which are what Badger and Cosgrove keep, and Suri, which are more rare and known for their silk-like fibers. Both produce 22 different natural colors of fleece, which means they don’t necessarily need dyeing. Alpaca fibers do not pill and are nonflammable and moisture wicking. And because they are lanolin-free, they are naturally hypoallergenic. Density, fineness, and crimp (a corrugated wave formation) are also valued characteristics.

Generally, the younger the animal, the higher quality the fiber—the first fleece, called the cría (Spanish for “offspring”), is usually the best. They are shorn every spring before the heat comes on. Shearing them is trying work—Cosgrove and Badger actually have a professional come in to do it. “It’s quite a process,” says Cosgrove. “We have to warn the neighbors.” The animals, a naturally fearful lot, make things rather difficult (and loud). They have to be tied to the ground, stretched out, and flipped from side to side to get the whole blanket.

At times, Badger and Cosgrove send their fiber to friends in Connecticut who also have an alpaca farm—from there it goes to a mill to be made into yarn or garments, which are then are sold in their friends’ farm store. They also know alpaca farmers in Vermont and on Martha’s Vineyard. “Alpaca farms are becoming a real tourist destination,” notes Badger.

These are notably clean animals—the whole pack defecates in the same location, latrine-like. Interestingly, some farmers and gardeners have started incorporating their pellet-shaped manure into their soils to boost nutrient levels. (Their waste is very nitrogen dense.) “It’s considered the black gold of the Andes,” chuckles Badger. “Their digestive system is very efficient—they have two stomachs—so you don’t have to compost the manure to use it. You can put these pellets straight into the garden.” Cosgrove notes that teaching people the value of it excites interest (and demand). “Why go to Home Depot for compost?” she asks.

Also in terms of education, Badger and Cosgrove have been known to host Girl Scout troops and schoolchildren to teach them about the animals. “We don’t mind sharing it—it’s like a show-and-tell,” says Cosgrove. “It makes it really fun—it’s not just the farmwork.” People are pretty wowed by the animals, which reminds the couple, once again, how special they are. The Scouts will send thank-you notes with hand-drawn alpacas—it is an experience that really stays with them. “It shows that it counts. A lot of people don’t get exposed to a backyard farm,” says Cosgrove, noting that there are many lessons afforded young people when working with and caring for animals.

Since their alpacas don’t produce enough fiber to work with on any kind of commercial scale, the garments the couple sells online are imported from Peru. “At this point,” Badger says fondly of his pack, “they are more a hobby. They are just part of my life now.”

978-912-7941