Growing up in Newburyport, Appleton Farms’ cheese maker Anna Cantelmo explains food was never a focus in her household. In fact, she describes it as almost an annoyance. It was more about fast and easy than artisanal and fresh—there were more important things to do than worry about where food came from. “It’s funny, both my brother and I now have careers that center on food—where it’s from and how it’s made,” she says. (Her brother David Coman-Hindy is a vegan activist and the executive director for the Humane League, a national farm animal protection nonprofit.)

It wasn’t until Cantelmo was 23 years old and working at Savenors, a gourmet butcher shop and cheese purveyor on Charles Street in Boston, that she was bitten by the foodie bug. “I loved learning about all the various cheeses,” Cantelmo says. “How cheese was made and what gave each cheese its distinct flavor fascinated me.” Cantelmo’s curiosity led her to take classes with some of North America’s premier artisan and farmstead cheese makers.

Over the next 10 years, she learned from Margaret Peters-Morris of Glengarry Cheesemaking in Canada, made goat’s milk cheese with Gianaclis Caldwell of Pholia Farm in Oregon, produced sheep’s milk cheese with Larry and Linda Faillace at Three Shepherds Farm in Vermont, and consulted with world-renowned cheese maker Peter Dixon. She learned about milk sources, separating curds and whey, microbial cultures and rennet (an enzyme used to coagulate milk), salting and brining, hygiene and sanitation, and the cheese aging and ripening process.

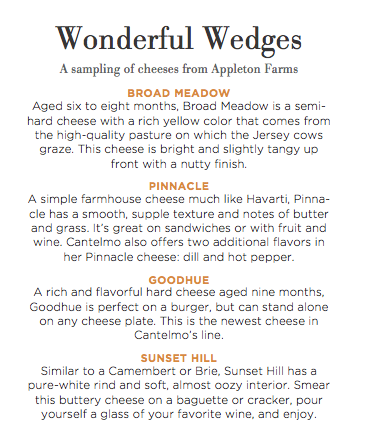

Cantelmo had an opportunity three years ago to return to the North Shore and work with cheese maker Arlene Brokaw at Appleton Farms in Ipswich, where the cheese is made from the milk of the farm’s Jersey cows and sold through the farm’s dairy store. When Brokaw moved to Maine, Cantelmo was promoted to head cheese maker. Today, she produces four types of cheese—three hard and one soft—in the former bull barn turned cheese kitchen, which today is reminiscent of a sterile laboratory.

With a joyful, serene aura, Cantelmo explains the cheese making process, pointing out the pipeline that delivers the milk from the dairy barn, the massive stainless steel vat where she separates the milk’s curds and whey, the round molds that form the cheese, and the refrigerators or “cheese caves” where the cheese is aged.

|

“I pasteurize the milk at a low temperature so it does not denature,” she explains. “I gently cook it at 145 degrees for 30 minutes to get rid of most of the natural bacteria, and then I add my own culture, which I know will taste delicious. This gives me a little bit more control— a blank slate to work with.” She stirs the culture into the milk, and when she has the right acidity, she adds the rennet. Once the liquid, or whey, separates out after about an hour and a half, she scoops up the curd, which almost resembles popcorn, and places it into the forms that are lined with cheesecloth to wick away moisture. The cheese is then pressed to create one solid rind. “Too much moisture can create bitterness in cheese,” notes Cantelmo. She then dry salts the cheese over a two-day period. Once this step is finished, the cheese goes into the 55-degree F. caves to age and ripen.

“Farmhouse cheese ages for four months—mold starts to grow the first month, so we brush or wash the mold off until the rind is established,” she notes. “The mold continues to grow on the rind, which ripens and flavors the cheese.” Resembling more of a science project than a delicious snack, each cheese is covered with different mold—B. linens, white Penicillin, Scopulariopsis. “It’s beautiful—it’s like suede to me,” she says, referring to the fungal shrouds covering the large wheels of cheese.

When asked what makes the cheese taste so good, Cantelmo exclaims, “The cows!” Dairy manager Scott Rowe has been on the farm for three years tending to the Jersey herd that grazes in the meadows of Appleton Farms—today there are 19 in total. Rowe explains that the Jersey cows produce the highest butterfat content, which gives Can- telmo’s Sunset Hill, a triple cream Camembert-style cheese, its rich buttery flavor. “This cheese is what Jersey cows were put on this earth for,” smiles Cantelmo. Jersey cows are also integral to the history of this 300-plus-year-old farm. In the 19th century, the Appletons brought Jersey cows to this county from England. In 1893, a heifer from that first herd was exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exhibition for yielding the record, up to that time, for the highest amount of butter produced in a single year by one cow—945 pounds, 9 ounces.

|

In 2011, Appleton Farms restored and rebuilt the dairy barn, milking stalls, and creamery needed to reintroduce dairy farming back to Appleton. The Trustees of Reservations (the organization that runs Appleton) also installed a pipeline to transfer raw milk from the bulk tank to the pasteurizers, as well as a butter churn, yogurt filler, and three refrigerated rooms for aging cheese.

Every morning, well before the sun peeks over the horizon, Rowe is on his way to milk the cows. His weathered and chafed hands speak volumes about the labor-intensive work of tending the herd, which produces just over 800 gallons of milk a week. (Their second milking of the day is at 2 p.m.)

Rowe has been working as a dairy farmer for 15 years. He does not use antibiotics on the animals, and the farmers tending the grass and hay fields use organic practices. “The cows are well cared for with low stress,” says Rowe. These brown-eyed creatures—each with a sweet name like Button or Daisy—are clearly loved: His philosophy is to give his cows the best life possible and a respectful death. He does not push for the most milk production but rather provides more targeted care. “Our cows continue to produce milk even after seven years when institutional farm cows might stop milking after two years,” he says. “The old ways of farming are not working. What The Trustees are doing is the future of the New England farm—creating a local, sustainable model is going to be the driver.” And with the fruits of his labor producing such delicious, local dairy offerings, I couldn’t agree more. thetrustees.com