Katie Banks Hone loved her location when her family moved into a midcentury Cape on the Ipswich River in 2011. Although the home sits on only one-third of an acre, it boasts 91 feet of scenic river frontage. But what didn’t thrill Hone was the lawn. An ardent gardener who previously spent a dozen years as an aquarist at New England Aquarium before becoming a stay-at-home mom, Hone is keen on all creatures great and small. The limited resources for wildlife in her yard were getting her down.

It didn’t take long for Hone to swing into action and reverse the ratio of grass to other plant life in her yard. The following spring, she applied for and received a U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service grant to add rain gardens and create native landscaping. Local regulations required that trees and shrubs could not be removed from the property without special permit, but her workaround was to add to the smorgasbord onsite and beef up the landscape with natives.

Meanwhile, the monarch population was imperiled. In fact, the 2013 census of monarchs in their Mexican winter migration home tallied the lowest population numbers ever recorded. Experts pointed the finger at the steady decline of fodder in the monarchs’ northern summer habitat as the culprit. Many people blamed agriculture for the situation, but Hone took it personally. Rather than waiting for action from big business, she championed the cause to increase insect habitat. Talk to Hone and she’s quick to point out that solutions start at home.

“That’s how I got into native gardening,” Hone sums up the first inklings. To repopulate her property with monarchs, as well as birds, bees, other butterflies, and bugs in general she swung into an ambitious planting spree. “We had to deal with masses of buried landscape fabric here when we initially arrived. Nothing grew. It was a complete desert.”

First on the agenda was to remove the fabric to give all things horticultural a fighting chance. Then she began remedial planting to heal the land. To achieve the number of plants needed to cover space formerly hosting nothing more than scraggly weeds, she focused on starting from seed. Watching as her landscape was transformed and knowing that she was adept at sowing seeds under artificial lights in her basement, friends began begging Hone to start seeds for them. Then her young daughters hatched the idea: Why not take her full-time hobby to the next level? It took only a season for a business to take flight. By 2014, she was selling seedlings at the local farmers market.

Katie Banks Hone calls her business the Monarch Gardener because she began with milkweed, which serves as the host plant for monarch caterpillars, as well as other plants that monarchs visit for nectar. But it became a much bigger picture than merely monarchs, or only butterflies. “Monarchs are a gateway species,” Hone likes to say. “Butterflies are big, colorful, and they don’t sting—so they’re good ambassadors. But I cater to the whole picture.”

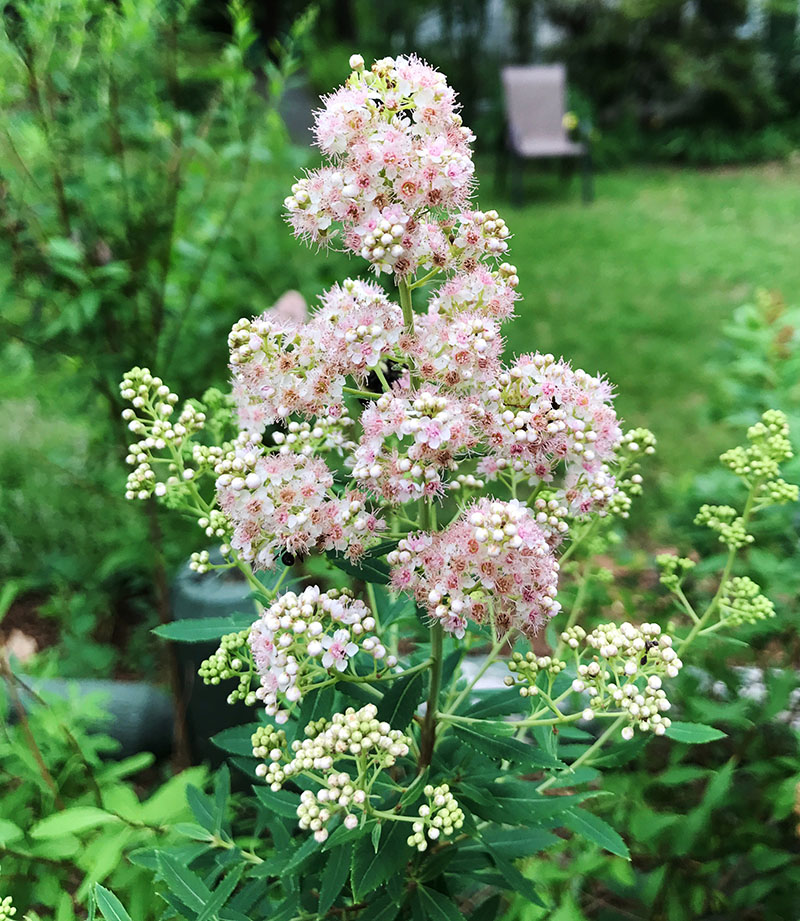

For Hone, that means furnishing a veritable cafeteria of native plants that lure insects of all types into her ecosystem. And it goes beyond bugs, because birds often feed on the bounty in her backyard. To play the good host, her goal is to nurture native plants that please pollinators throughout the growing season. For earliest spring, she suggests bloodroot, violets (“very important for fritillary butterflies”), spicebush (lindera, which she advocates as a native forsythia alternative), Virginia bluebells, beach plum (“which hosts hundreds of moth and butterfly species”), and golden Alexanders. Midsummer performers include echinacea, lobelia, wild geranium, and penstemon. Later in the season, she provides bee balm, asters, goldenrod, rudbeckia, and joe-pye weed as well as many other pollinator-pleasing species.

Because she is dedicated to serving up the precise menu that local insects and birds prefer, Hone now collects seed on the nearby land of friends and neighbors who have given her permission to forage. That way, she has honed fine dining from a bug’s perspective, catering to local ecotypes. Surprisingly, she finds that some of the most common plants have become bestsellers. For example, the Monarch Gardener offers five species of goldenrod, and they tend to sell out in a blink when Hone takes her wares to market.

Currently, the Monarch Gardener makes its seedlings and shrubs (grown in larger borrowed fields) available at a roadside stand in Hamilton on Fridays and Saturdays from spring through early summer. Business has been brisk. “Everyone wants to do something, and it doesn’t take much to flip the equation in favor of pollinators,” Hone enthuses.

She finds that few customers need convincing nowadays. But if anyone is skeptical about diminishing populations, all she needs to ask is, “When was the last time you scraped bugs off your windshield?” She also points out that going the seedling route is an economical way to do your part. “Seedlings cost only four or six dollars, and it’s fun to watch them grow.” Hone should know. Her Ipswich property that was formerly a food desert from a pollinator’s perspective is now a feast for all things flying.