Three years ago, artist Zarah Hussain could hardly breathe.

“I was coughing, I was having trouble walking uphill, and I just wasn’t getting enough air into my lungs,” she says in a Q&A with the Peabody Essex Museum. It turned out to be an issue with her diaphragm, and after corrective surgery, she had to learn how to breathe again.

During her healing process, she began painting—visually conveying how her lungs felt as they relearned a basic function that most of us take for granted. That was, until about a year ago.

In 2020, COVID-19 swept the world. And Hussain brought out her old paintings about learning how to breathe as another tragedy came center stage—the killing of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police. Some of George Floyd’s last words were “I can’t breathe.”

The response to the U.K. artist’s painting series on breathing was overwhelmingly positive. “People were contacting me from the States, from Europe, from India, all over the world,” says Hussain. “It kind of touched a nerve.” Compiled into a new exhibit at the Peabody Essex Museum, Hussain’s paintings are accompanied by an animation and a soundscape in Breath, on view through June 20, 2021.

Hussain, daughter of immigrants to the U.K., takes most of her artistic inspiration from geometry. “[We had] pictures of mosques, we had carpets, we had a few things from India and Pakistan,” Hussain says of growing up, “and I loved the geometry and repeating patterns.”

“Hussain’s work lies at the intersection of science and spirituality and melds ancient traditions of meditation and breathwork with contemporary technology,” says Siddhartha V. Shah, PEM’s director of education and civic engagement and curator of South Asian Art. “It’s really powerful and profound work. It’s definitely multidimensional.”

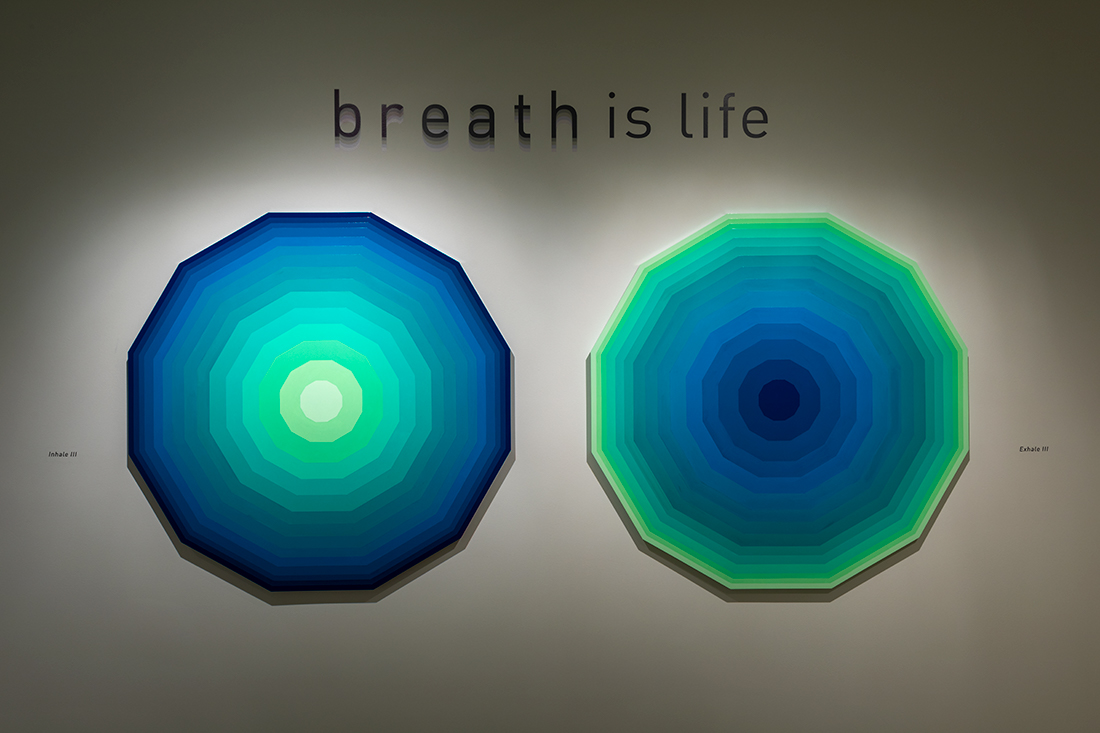

“By the latest research I’ve looked at,” explains Hussain, “the perfect breath is 5.5 seconds. It’s a deep breath—5.5 seconds in and 5.5 seconds out.” After just a few minutes, these breaths begin to soothe the body. Hussain has artistically represented her “perfect breath” through the three elements of the Breath exhibit: painting, animation, and sound.

The exhibit immerses viewers in a tide of inhales and exhales, and encourages them to follow along. You’ll see Hussain’s paintings of the visualization of breath, which she calls a sort of “holy geometry,” and you’ll also experience an evocative animation and soundscape, encouraging you to experience your own “perfect breath.”

“We live in a world where we are constantly on,” says Hussain. “There is such a benefit to just slowing down and being quiet.”

Growing up, although Hussain remembers being fascinated by art class, she never learned about non-Western art until a postgraduate program she took at the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts. “We never looked at anything beyond the West, this tiny little area. I was aware that there was something beyond what we were being taught,” she says. “I just knew when I looked at these beautiful mosques, there had to be a theory… a way of understanding it, of deconstructing it.”

Hussain holds equal space for her loves of geometry and traditional Islamic art, and of coding and computers. “There’s a lot of sympathy with Islamic art because it’s based on math and algorithms,” she explains.

But Hussain has employed math and algorithms so efficiently in the Breath exhibit that all you’ll notice is the calming energy of the shapes and sounds synchronizing with the perfect breath.

“The ancient traditions I’ve looked at [including Chinese qi and Indian prana] say you shouldn’t measure your life by the days and the hours—you should measure your life by the breaths you take,” says Hussain. “Because the longer and the slower and the calmer the breaths are, the better quality of life you have. And it’s about quality of life, not length of life.”

For more information, visit pem.org/exhibitions/zarah-hussain-breath.