Six off-the-beaten-path museums to help stave off the winter blues. By Tamsin Venn

Any of us have visited the most famous museums of the North Shore with out-of-town guests or relatives in tow. We have climbed the hidden staircase at The House of Seven Gables, wandered dim rooms in the Huang family ancestral home at the Peabody Essex Museum, and viewed Fitz Henry Lane’s luminous harbors at the Cape Ann Museum.

But dotted across the North Shore between those stars are other gems that highlight particular pasttimes or eras, celebrate their owners, or simply hang selected works by the masters or feature quirky collections of objects generously donated by North Shore residents.

When in the mood for an afternoon jaunt this winter, avoid the crowds at the bigger museums and check out these local treasures instead.

Boott Cotton Mills Museum

When Boston merchants, who first experimented with fabric mills in Waltham, needed more power than the sluggish Charles River, they moved to Lowell, not only because of the powerful 30-foot Pawtucket Falls, but also because they could take advantage of Pawtucket Canal built around the falls in the 1790s.

The Boston Associates created Lowell in 1826, naming it in memory of colleague Francis Cabot Lowell. The most palpable reminder of the 10 brick mill complexes that once lined the Merrimack River and the million yards of cotton cloth they churned out is the Weave Room of the Boott Cotton Mills Museum, located in a mill built in 1836. Here operates a fraction of the 88 looms from a 1910 factory, with the pounding metronome of the cotton weaving, loud enough for the use of earplugs. Upstairs, interactive exhibits and oral history videos cover the Industrial Revolution and Lowell’s working people.

Starting in March, take the 90-minute Working Canal Tour by boat, and you’ll experience first-hand what Henry David Thoreau called the “Manchester of America, which sends its cotton cloth around the globe.” Ride the Francis Gate Guard Locks along the Pawtucket Canal and see the great 21-ton drop gate designed by Lowell engineer James B. Francis, which saved the city from flooding in 1852 and again in 1936.

Location: 115 John St., Lowell, 978-970-5000, nps.gov/lowe. Winter hours: Visitor Center (246 Market Street), 9-4:30; Boott Mill, 9:30-4:30. Admission: Adults, $6; children 6-16 and students, $3; senior discount; children 5 and under free. Free parking behind the Visitor Center, next to Dutton Street.

Ipswich Museum

Ipswich has more “First Period” houses-those built before 1725-than any town in the country. The one you can visit without a dinner invitation is the Whipple House, built in 1677. Across the street is the handsome Federal Heard House. Both are run by the Ipswich Museum (IM), created when Ipswich Historical Society members voted to transform and invite everyone in, not just the elite. “Society seemed exclusionary or closed; [the] museum [is] more open and friendly,” says director Wendy Evans.

The Whipple House has four rooms and a cobbler’s shop that illustrate family life in the early colonies. Highlights include Gaines chairs, period blanket chests, and a Dennis chest. The Heard House shows how far the colonists progressed in just a century. On view are China Trade treasures collected by the John Heard family on voyages East and paintings by Ipswich native Arthur Wesley Dow (1857-1922). Dow was one of the most influential art teachers of the early 20th century, and IM owns the largest single collection of his works, including oil paintings, watercolors, woodblock prints, photographs, cyanotypes, and plaster molds.

A new gallery guide informs visitors about other artifacts throughout the museum: items from the Ipswich Female Seminary, Civil War memorabilia, 19th-century dresses, 18th-century lace made for sale by Ipswich women, carriages, and a copy of Anne Bradstreet’s 1678 “Several Poems.” Under construction is the one-room Knight House, showing the miniscule size of first settlers’ homes.

In December, visitors can view “Perspectives on Nature,” presented by members of the New England Society of Botanical Artists. Late January brings “Ipswich Furniture of the Dennis Chest Era,” which focuses on the recent purchase of a second Dennis chest made in Ipswich in 1690 by Thomas Dennis, Jr., son of Thomas Sr. and considered the most important joiner in 17th-century America.

Location: 54 South Main Street, Ipswich, 978-356-2811, ipswichmuseum.org. Hours: Wednesday, Thursday, 10-3; Friday, 12-3; Saturday, 1-5; Sunday, 1-4. Heard House: October-April, Sundays, 2-4. Admission: Adults, both houses, $10; one house, $7; children 6-12, $3; children under 6, free.

Wenham Museum

“[The Wenham Museum] is a family-friendly, hands-on history museum that celebrates childhood and family life,” says executive director Lindsay Diehl. “We really want to engage our visitors and help connect them to history… For many children, this is their first idea of history.”

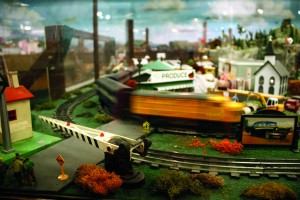

The Bennett E. Merry Train Gallery runs nine model trains in various gauges by push button. Curator Rob Flanagan will show you how to set up a model train, create scenery, and keep the trains running. Through February 20, the Train Time exhibit fills the museum with train models, including the New England Limited passenger train of 1891, which was nicknamed the Ghost Train for its white cars and high speeds as it traveled the twilight route between Boston and New York.

The Bennett E. Merry Train Gallery runs nine model trains in various gauges by push button. Curator Rob Flanagan will show you how to set up a model train, create scenery, and keep the trains running. Through February 20, the Train Time exhibit fills the museum with train models, including the New England Limited passenger train of 1891, which was nicknamed the Ghost Train for its white cars and high speeds as it traveled the twilight route between Boston and New York.

But step aside, trainiacs. At any one time, the museum has 1,000 dolls on display (out of 5,000 dolls and toys in the collection). The museum was founded in 1922 by the Wenham Village Improvement Society, and the last girl to grow up in the house (which became the museum) was Elizabeth Richards Horton, who donated her collection of 800 dolls to the Improvement Society, which eventually became the Wenham Museum. The figures include Shirley Temple, Lady Betty Modish in a complete Edwardian outfit, suffragist Julia Ward Howe, and even a Boston Red Sox player. Most famous is Miss Columbia, who circumnavigated the globe in 1900 on a good will mission and whose journal, “My Trip Around the World,” can be viewed on the museum’s website.

To give the collection even more appeal, Horton solicited dolls and dollhouses from world leaders like Tsar Nicholas II and Alexandra, Queen Victoria, the Queen of Hawaii, and the Empress of Japan. Several dollhouses have miniatures worth more than regular-sized furniture. Princess Belosselsky’s dollhouse includes a tub by Crane Plumbing, and a TV on whose screen Addams Family members Lurch, Mortitia, Gomez, and The Thing pose for ghoulish action. In cases are entire armies of lead soldiers, as well as banks, games, paper dolls, miniatures, and teddy bears.

The attached Claflin-Richards House is a First Period home that displays furnishings and objects from four different eras, from the 1660s to the 1840s. Mary Thorn’s woolen bed rug (ca. 1724) is the second oldest such rug known to exist in the U.S. “We like to use the house for children to compare the way we live now versus then,” says exhibits curator Jane Bowers.

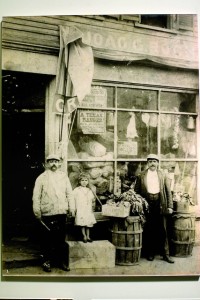

A costume collection of 10,000 pieces rotates seasonally, overseen by Linzee Jerrett. Benjamin Conant’s 3,000 beautiful glass plates depict children, families, homes, and businesses in the Wenham area from 1890 to 1918.

In the Family Discovery Center, “Boom! We’re History: American Family Life 1946-1964” lets children dial a rotary phone, peck at the keys of a typewriter, and play a record on a phonograph.

Pick up an activities kit at the front desk; graphic red and green hands alert children to what they can touch and play with in this child-friendly space.

Location: 132 Main St., Wenham; 978-468-2377; wenhammuseum.org. Hours: Tuesday-Sunday, 10-4, closed major holidays. Admission: Adults, $7.50; children, $5.50.

Essex Shipbuilding Museum

The first generation of Chebacco colonists resorted to fishing after experiencing the difficulty of farming on the rocky New England soil, the abundance of clams for bait, and the abundant cod that ran in Ipswich Bay just five miles away. Using the white oak that grew nearby, the early residents made their own fishing boats, and by 1668, shipbuilding had become an industry. Since that time, the ramp by the museum has been used to launch ships into the Essex River. The colony of Chebacco, renamed Essex in 1819, became one of the biggest shipbuilding centers in early New England. Thanks to the many Essex shipbuilding descendants, the museum has a large and interesting collection of artifacts. Essex launched close to 4,000 vessels, and just seven are still in existence, including the Evelina M. Goulart, anchored on museum grounds.

Learn about Arthur D. Story’s impressive shipyard production, the continuation of the Essex tradition under Harold Burnham, and how to “frame up” a vessel. In the classic 1947 film Shipbuilders of Essex, watch some of the last old-time Essex shipbuilders produce a 70-foot fishing vessel for the Gloucester fleet. You can also go inside the former paint shed and learn about how wooden vessels are fastened with wooden pegs called trunnels. Try your hand at caulking with a mallet and iron with strands of cotton and oakum. If you still have time, visit the 1835 School House and Burial Ground and Hearse House.

The Lewis H. Story was built on the site in 1998 and is often seen at the museum or at nautical events throughout New England.

Location: 66 Main Street, Essex, 978-768-7541, essexshipbuildingmuseum.org. Hours: November–May, Saturday and Sunday, 10-5; June-October, Wednesday-Sunday, 10-5. Admission: Complete guided tour (includes schoolhouse collections), adults, $7, seniors, $6, children 6-18, $5. Self-guided tour with shipyard map: adults, $5.

Custom House Maritime Museum

This museum occupies the granite Custom House, built in 1835 and designed by Robert Mills, who also designed the Washington Monument and the Treasury Building. The wrecking ball almost demolished the building in the late 1970s, but a few visionaries saved it to tell the story of Newburyport and its seafaring, including its own anchor in history as the birthplace of the Coast Guard.

In 1790, Alexander Hamilton placed the first station of the Revenue Service (precursor to Coast Guard) in Newburyport to track and tax cargo. In the Coast Guard Room, you will see ship models, uniforms, and historical documents. In the spring, the museum hosts an exhibit on the SPARS, the women’s division of the Coast Guard from 1940-47.

Newburyport sent ships all over the world, even though its port was one of the most dangerous to exit, requiring navigation through the treacherous Merrimack River. The Shipwreck Room documents that danger, with salvage items and photos. Upstairs, see the exquisite quilt of Alice Brown, daughter of Newburyport sea captain Laurence Brown. Made of fabrics collected on her travels, the quilt uses stitches unusual in New England quilts.

Another room is devoted to native author and Pultizer Prize-winner John P. Marquand, where you can see his portraits, books, and typewriter. Descended from sea captains, Marquand set three of his novels in a thinly disguised Newburyport.

The Moseley Gallery features The Hall of Ships. It includes ship models built by John Currier and designed by Donald McKay, including the Dreadnaught, the most famous clipper ship built in America. Another model is of the Swedish warship Vasa, which sank in 1628 after sailing only 1300 yards. See models made by amateurs from New England clubs, thanks to Bill Partridge, owner of the Piels model boat shop just across the street. Partridge’s favorite item in the museum is the bone schooner, crafted by a prisoner of war from soup bones.

*Photo Courtesy of the Custom House Maritime Museum, Newburyport

Location: 25 Water St., Newburyport, 978-462-8681, customhousemaritimemuseum.org. Hours: Open May 15-December 15. Tuesday-Saturday, 10-4; Sunday & Holiday Mondays, 12-4. Admission: Adults, $7; seniors and students, $5. Free for active military members and children under 6.

Addison Gallery of American Art

Thank Thomas Corcoran for one of the best early American landscape art collections in the country. A trustee of Phillips Academy, Corcoran wished to invest in the “love of the beautiful” for the boys. In the 1920s, he hired a New York dealer who bought the best available.

The Addison reopened in September after a two-year renovation and expansion project. A new 13,000-square-foot education center funded by Andover alum Sidney R. Knafel has a library, a classroom, storage, offices, a loading dock, and the first green roof in Andover, carpeted in sedum and “Black Niijima Floats” by glass artist Dale Chihuly. The graceful rotunda has been restored, and Paul Manship’s Venus fountain now gurgles water. All the galleries have been restored but otherwise unaltered. “We weren’t going to change the small, intimate feel of the gracious and welcoming galleries,” says museum director Brian Allen. “People can very easily take ownership of the spaces and we don’t want to tamper with that.”

The Addison reopened in September after a two-year renovation and expansion project. A new 13,000-square-foot education center funded by Andover alum Sidney R. Knafel has a library, a classroom, storage, offices, a loading dock, and the first green roof in Andover, carpeted in sedum and “Black Niijima Floats” by glass artist Dale Chihuly. The graceful rotunda has been restored, and Paul Manship’s Venus fountain now gurgles water. All the galleries have been restored but otherwise unaltered. “We weren’t going to change the small, intimate feel of the gracious and welcoming galleries,” says museum director Brian Allen. “People can very easily take ownership of the spaces and we don’t want to tamper with that.”

In November, the Gallery shows the work of Sheila Hicks, an American textile sculptor with influences of Paris and Santiago, Chile. In January, an exhibit by painter and stained-glass-window maker John La Farge takes residence. Artist in Residence Tristan Perich’s multimedia installation is on view in the Museum Learning Center through March 27.

Location: Campus of Phillips Academy Main Street and Chapel Avenue, Andover, 978-749-4015, addisongallery.org. Hours: Tuesday-Saturday, 10-5; Sunday, 1-5, closed Mondays and national holidays. Free admission.