Walk into Olivia Parker’s seaside studio and the first thing you notice is that the outdoors has been brought in—shells, feathers, and assorted bits of organic matter. Parker has been a big fan of the natural world since her childhood in the Boston area. Later, moving to Manchester-by-the-Sea with her husband in 1967, she took daily walks to gather kelp, driftwood, and shells of all shapes and sizes.

These natural bits can be glimpsed in PEM’s current exhibition, Order of Imagination: The Photographs of Olivia Parker, the first retrospective of the celebrated photographer’s work. Parker’s photography is represented in a number of major collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, and PEM, where visitors will find more than 100 intricately composed photographs that reflect the artist’s wide creative range and unflagging curiosity, on view through November 11.

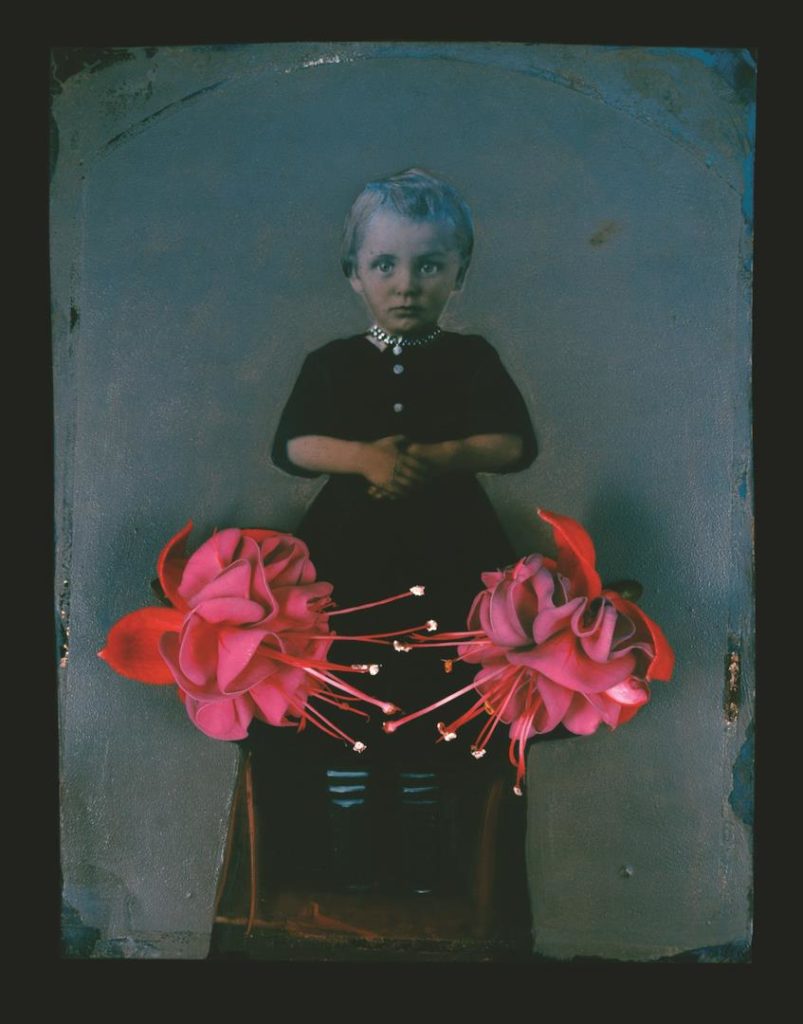

For more than 40 years, Parker has created poetic and dreamy photographs that make us re-examine the familiar. Resisting any temptation to photograph the nearby woods or beaches, Parker prefers to experiment in her studio, mostly shooting downward toward her floor, where objects are arranged on paper, with natural light passing through the south-facing windows of her studio in the home she has lived in for more than 50 years. “It’s a matter of how the object reacts with light more than the object itself,” says Parker, who calls the reflective qualities of a broiling pan “fabulous.”

A found object may wait in her studio for decades before it’s picked up and put before the camera. When she was at home with two young children, she worked with what was on hand. It wasn’t until later that she started going to flea markets, such as Todd Farm in Rowley, where she recently came across glass fishing floats. “They’re the biggest ones I’ve ever seen and they’re crusted with barnacles and I really like them,” she says with a mischievous smile.

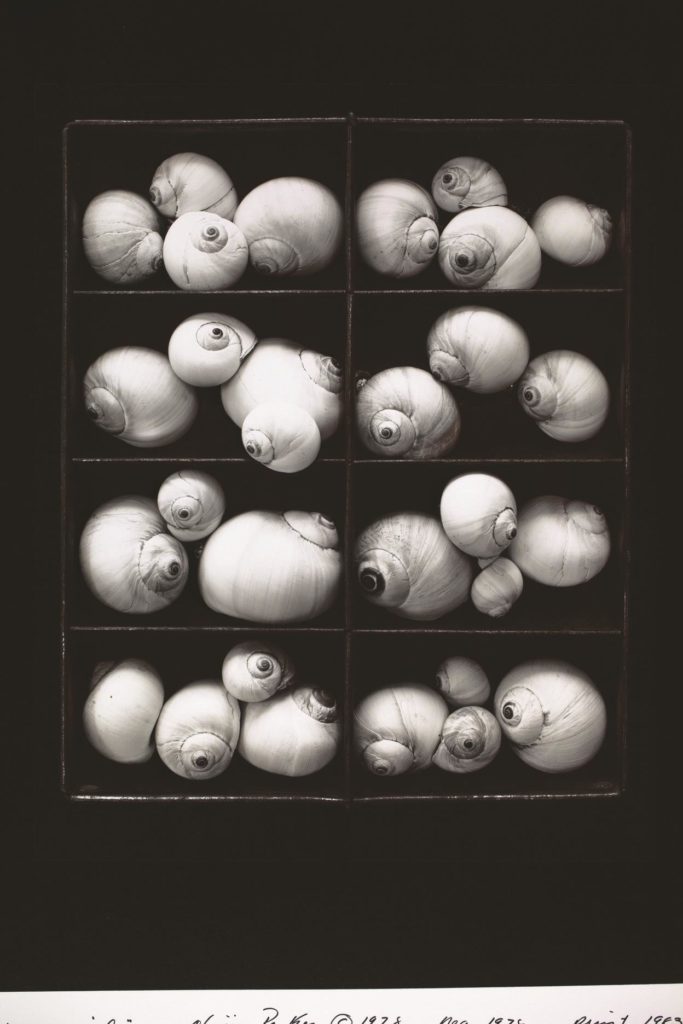

Among her treasures is a drawer of bones, big chunks of glass that reflect the light nicely, as well as jewel-toned glass bottles, old sepia negatives of strangers, small plastic figures, and collections like a glass vase full of rubber bulb ear cleaners. One intriguing piece, haunting in its beauty, and surprising in its simplicity, is Moonsnails, an arrangement of snails in a corn muffin tin. Parker says she pushes objects around, arranging them just so.

“I know intuitively when something is going right,” she says. “Sometimes it may work from a visual point of view, but it’s not saying something to someone or to me. So it gets tossed out.”

Her early training as an art historian and painter has resulted in particularly moody works reminiscent of the still-life paintings found in 17th-century Dutch and Spanish traditions. Her work reflects whatever Parker is reading at the moment and the things that she’s deeply curious about, which includes the history of both science and art. “The parallels are amazing,” says Parker. “People who are making art are going off the edge of a map, which is very similar to people doing scientific research—they’re going off the edge of a map, too.”

In 1995, a skiing accident left Parker on crutches for a year, unable to work in the darkroom or studio. She set her sights on learning the emerging technologies of digital composition and editing. Her 1996 photograph The Murderer’s Brain features an actual brain in a jar that was removed from a convicted murderer from the 19th century, when scientists thought the brain had physical characteristics that would indicate a penchant for violence. Next to it is a page from a book on phrenology, the pseudo-science popular in the same century that associates human character with the shape and appearance of the skull. Three profiles to the left are from a 16th-century treatise that compared human faces to animals as a way of assigning character traits. “Theories abound, and I’m always fascinated about how far to the side they go,” says Parker.

Some of her latest work was inspired by both science and the brain. In 2013, her husband, John, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. After he went to a care facility, Parker started running across the stacks of notes John used to help him remember and they provided some insight into what he was going through.

One of them is a list of the places the couple had visited on their honeymoon. “I put it in this light and photographed it and printed it a couple of different ways, and it seemed something was there,” says Parker. “I can’t know what John was thinking. It’s really my imagination on his illness. I was continually experimenting, pushing to see how far I could take this idea.”

She used glass bottles to make streaks of colored light across the notes that suggest impermanence or “flashes of lucidity,” explains the photographer, who is realizing how much the series on her husband’s illness has helped other people, especially caregivers. Throughout her life, Parker has managed to pivot her work to adjust to new circumstances.

With its large photography collection right down the road from her, Parker has decided to gift the works from the current exhibition to PEM. In the meantime, she will get back to work, finding a certain peace and resilience in the depths of her own imagination.

For more information, visit pem.org; oliviaparker.com.