Next year, America will celebrate the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower landing at Plymouth Rock. Although they fled Europe to escape religious oppression, the Puritans initially established a stringent theocracy that persecuted nonbelievers and believers alike. Attending worship was mandatory. Strict piety in faith and conduct was obligatory. This conservative milieu bred the infamous Salem Witch Trials almost three-quarters of a century later.

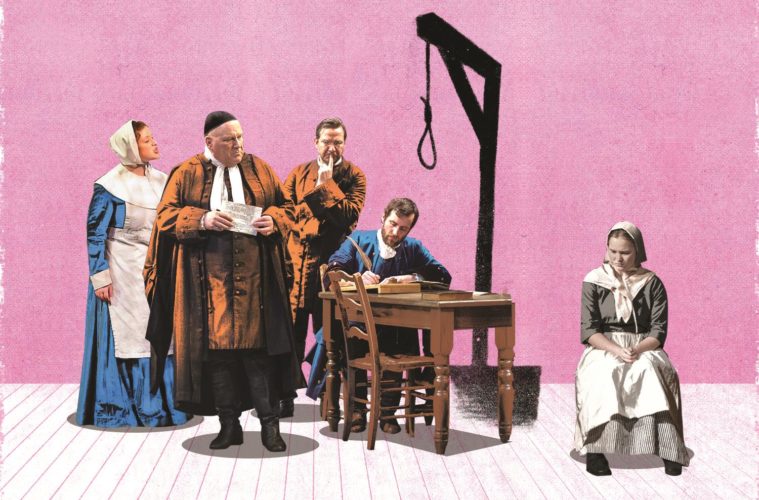

Arthur Miller captured the fervor of this period in his 1953 play The Crucible. It is pertinent to note that Miller’s masterpiece is a work of historical fiction, although it is true to the spirit of the trials. Many of the conversations between the characters are his conjecture. He also took some liberties in terms of ages and names. In his introduction to the play, Miller admits that he raised the age of the play’s antagonist, Abigail Williams, from 14 to 17, and that he combined several of the justices into two: Hathorne and Danforth.

Still, the play retains its permanence, because it remains relevant. Critics see the piece as a polemic against the McCarthy hearings of the 1950s.

The play premiered on January 22, 1953, as Senator Joseph McCarthy was accusing actors, composers, academics, military officers, union leaders, writers, and, most notably, political colleagues of being communists. The term “witch hunt” was even associated with McCarthy’s crusade, also dubbed the Second Red Scare—one in which just an accusation from the Wisconsin Republican was enough to blacklist those in his crosshairs. “McCarthyism was in the air,” writes literary critic Thomas E. Porter, “and it had all the qualities—for those personally affected—of the witch-hunt.” Porter continues: “Miller consciously draws the parallels; his plays are efforts to deal with what was ‘in the air.’”

Whereas Miller’s medium was the pen, McCarthy seized the airwaves. Still in its infancy, television enabled Americans to tune-in to the McCarthy hearings between April and June 1954 when they weren’t watching “I Love Lucy” or “The Milton Berle Show.” Miller himself was held in contempt of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in May 1957 for refusing to identify industry associates who were suspected communist sympathizers. One hears Miller’s resolve foreshadowed in the voice of his character Giles Corey: “I cannot give you no name, sir, I cannot.” The charge was overturned a year later, for Miller had been misled by the committee chairman, Representative Francis E. Walter (D-PA), who promised the playwright that he would not have to name names in his testimony.

Originally entitled Those Familiar Spirits, the play’s name change is more apropos, as a crucible is a severe test or trial. It is also a container in which metals are subjected to extreme heat in order to form an alloy. In Act Three, Deputy Governor Danforth intimates both definitions in his admonition of the play’s protagonist, John Proctor: “We burn a hot fire here; it melts down all concealment.”

The careful reader will inquire: To what extent were these witch hunts fueled by economic vengeance as opposed to spiritual fears? In Act One, Corey—whose famous last words were “More weight” when pressed to death at the end of the play—insightfully observes, “It suggests to the mind what the trouble be among us these years…Think on it. Wherefore is everybody suing everybody else?” Miller notes how ubiquitous lawsuits and land disputes between the Putnam and Nurse families, for example, made the citizens of Salem Village (now Danvers) overly rancorous of one another. What better way to seek revenge on a family with whom you were embroiled in a property claim than to accuse them of witchcraft?

Such vengeance is articulated at the end of the second act. Proctor, who in Miller’s play was involved in a sexual tryst with his maid, Abigail Williams, says, “Vengeance is walking in Salem. We are what we always were in Salem, but now the little crazy children are dangling the keys of the kingdom, and common vengeance writes the law.” These words are spoken in defense of Proctor’s wife, Elizabeth, who is arrested for witchcraft. Although Elizabeth would be given a stay of execution because she was pregnant (she was exonerated a year later), 19 innocent people, in addition to Corey, were hanged for refusing to confess to witchcraft.

In the play, as well as the annals of history, a group of young girls, under the leadership of Williams, becomes the center of the controversy. Having been influenced by tales told by Tituba, Rev. Parris’s Barbadian slave, the girls begin acting strangely. When they are caught dancing naked in the woods one night by the town minister (Parris), the coterie of girls deflects punishment by concocting stories that certain women in the town are forming pacts with the devil. Contrary to logic, their indictments were taken as law.

The Crucible has been performed on stages across the world. It has also been made into several film and television adaptations, as well as an opera by Robert Ward in 1961. The latter won both the Pulitzer Prize for Music as well as the New York Critics’ Circle Award.

But the play is about more than late-17th-century Salem or mid-20th-century Washington. At its heart, The Crucible speaks of individual conscience in the face of societal conformity. It is a story about thinking critically in the midst of popularized misinformation and allegiance to superstitions.

Proctor remains true to himself and his beliefs when faced with the madness that enveloped Salem. He will not acquiesce to the hysteria, even though it is sanctioned by those in power. Proctor employs reason and thinks for himself, which distinguishes him from the madness of the mob. He is even willing to die for what he knows to be true.

This is a pertinent lesson for us as we approach the third decade of the 21st century. In an age when we are becoming more divided politically—an era in which bipartisanship has become a byword—Arthur Miller teaches us to think for ourselves and rise above the fashionable talking points emanating from the right and the left.

Furthermore, each generation produces a scapegoat to bear the blame for whatever frightens them. The practice did not end in Salem Village, nor with McCarthyism. The LGBTQIA+ community was blamed for the AIDS epidemic (originally called “gay cancer”) when it was discovered in the early 1980s. Muslims were harassed in the wake of the September 11 attacks. Today, immigrants and refugees, seen as a monolith, are viewed with suspicion.

The origins of racism, homophobia, misogyny, xenophobia, classicism, and every other plague that infects the human heart are ignorance and fear. Neil Peart, drummer and lyricist for the progressive Canadian rock trio Rush, captures this sentiment best in the final line to their aptly titled 1981 song, “Witch Hunt”: “Quick to judge, quick to anger, slow to understand / Ignorance and prejudice and fear walk hand in hand.”